A field report by Emma Tennent and Fiona Grattan

We all know how important it is to protect participants’ confidentiality, particularly when working with sensitive data. However, ethics committees are not always familiar with how interactional research works which can pose challenges for data collection. In this short commentary, we report on the challenges Fiona faced in negotiating with the ethics committee and how constraints imposed shaped the process of data collection. We highlight the need for researchers of social interaction to share our strategies for securing ethical approval.

In the space of a 12 months Masters’ research project, Fiona Grattan spent five months in negotiation with our university’s ethics committee about how to collect data from the student health and counselling service. Fiona investigated the work of medical receptionists in handling incoming calls from students and had initially proposed to follow practices developed in other conversation analytic studies, that would inform callers of recording for research (e.g. Tennent, 2019). However, the ethics committee imposed conditions on data collection based on fixed assumptions about how consent should occur that we argue can pose undue time burden on participants and overestimate potential harms.

Fiona initially proposed that a pre-recorded message inform callers of recording and the research, with the opportunity to opt-in or out of the research. This method has been used successfully in research and is common practice in a number of institutions including health services which do not always provide an opt-out option (see Speer & Stokoe, 2014).

However, the ethics committee deemed this consent process insufficient and instead required three steps to secure consent:

- The pre-recorded message informed of recording for research and indicated Fiona would contact callers to discuss their participation.

- Receptionists confirmed callers understood the call had been recorded and that Fiona would contact them.

- Fiona attempted to contact the callers (up to three times) to read out the information sheet and secure oral consent to have their recorded call included in the sample.

The pre-recorded message

The pre-recorded message Fiona initially proposed was over a minute long which the ethics committee deemed a possible barrier to accessing service. Thus, the revised message began with a prompt to allow callers to skip if their call was urgent. Information about the project was omitted, with Fiona to explain this in person in a follow-up call.

Receptionists’ confirmation check

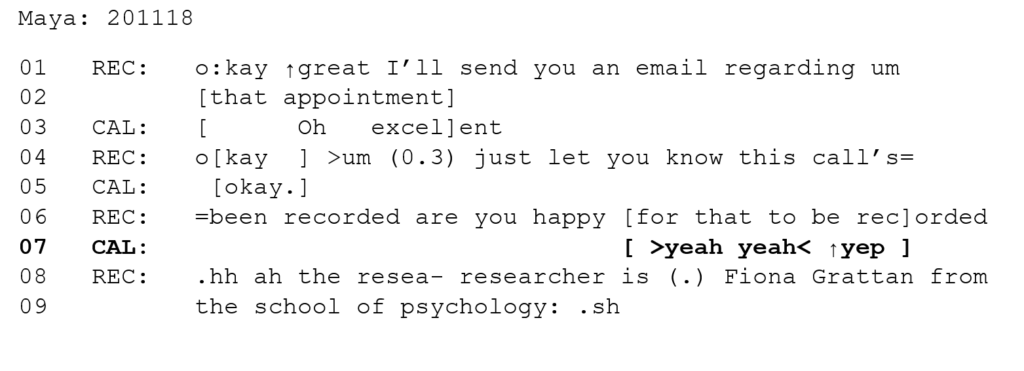

Receptionists did not always carry out the confirmation check as it had been specified by the ethics committee which resulted in otherwise usable calls being excluded from the sample. Data-internal evidence indicates that callers treated this step in the consent process as unnecessary. For example, in the extract below, the caller’s multiple saying (Stivers, 2004) “>yeah yeah< yep”, (line 7) treats confirmation as a course of action which should be rightly halted.

This case was presented to ethics committee as evidence that participants themselves were treating this step as unnecessary. In response, the committee agreed to this step being omitted for following data collection.

Follow-up call

Follow-up calls were only allowed if callers confirmed their phone number during the call itself. Fiona attempted to contact patients up to three times, but patients were non-contactable more than half of the time, which resulted in further viable recordings being excluded from the sample.

Although most calls to the practice lasted less than two minutes, follow-up calls regularly lasted five to ten minutes. Although one caller did choose to have their recording removed, arguably opportunities to withdraw from the study would have been possible with a more timely consent process.

Reflections

It is crucial to provide adequate opportunities for consent to participate in research. However, there is a tension between processes for securing informed consent and the practicalities of collecting naturally occurring social interactions. In Fiona’s case, the enforced consent process made it practically impossible to collect a credible sample of calls, undermining the ability of the research to provide possible benefits to students and the organisation.

Default assumptions about how informed consent should occur meant that the recorded message was treated as less suitable than a call from the researcher. In doing so, the committee overlooked the interactional dynamics and potential risks involved in securing consent in a follow-up call. This is not to call into question Fiona’s integrity as a researcher, but to recognise the basic interactional demands of the situation. Fiona’s calls were not recorded so we cannot analyse them directly. Nonetheless, we would suggest it is more interactionally difficult to turn down a request to participate in the here-and-now of interaction – when speaking to someone with a vested interest no less – than it is to respond to a pre-recorded message. As interactional researchers, we have a unique perspective on these challenges which we believe ethics committees should take into account.

Fiona’s experience with our ethics committee made apparent that guidance for qualitative research – at our university at least – is based on interview methods. Despite attending committee meetings, Fiona was given little space to argue her case. Initial suggestions to contract an external transcription service or to hire actors to recreate phone calls demonstrated the committee’s utter unfamiliarity with the theoretical justification behind our research methodology. The committee’s narrow focus on potential harm overlooked the benefits of empirical observational research, which is particularly striking given recent student dissatisfaction with overstretched health services.

Reform of ethical committees is unlikely, given their position within the institution of universities. However, as a community of interactional researchers, we can be strategic in our approach and share our experiences. The EMCA wiki is compiling ethical applications and protocols and we encourage readers to share their own resources to add to this database. Please contact the admins@emcawiki.net

Further Reading

This special issue in Human Studies focuses on ethics and interactional data.

References

- Speer, S. A. & Stokoe, E. (2014). Ethics in action: Consent-gaining interactions and implications for research practice. British Journal of Social Psychology, 53(1) pp. 54–73. doi:10.1111/bjso.12009

- Stivers, T. (2004). “No no no” and Other Types of Multiple Sayings in Social Interaction. Human Communication Research, 30(2), 260–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2004.tb00733.x

- Tennent, E. (2019) Identity and help in calls to victim support. (Doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10063/8262

What is a field report?

One of the joys of EMCA research is that we can collect data from anywhere and everywhere. The Field Report section is a place to share stories ‘from the field’. Fieldwork and data collection are crucial steps in the research process but the intricacies of what goes on are seldom fully reported on. In this section we will share tales of the joys, challenges, and surprises of fieldwork, hurdles or unexpected possibilities for data collection, and share our processes and strategies in a quest for greater transparency.Call for contributions

We welcome any stories of data collection or fieldwork that may be of interest to readers. Collecting data in a new or challenging context? Faced challenges in the field others should know about? Send us a brief report (up to 1000 words) for an upcoming publication.Please email your contribution to pubs@conversationanalysis.org

Great discussion. I can totally under endorse the idea that it’s harder to say no to an ethics request face-to-face than it is when dealing with a pre-recorded message. In some of the data I’m using (secondary analysis), we had full consent for almost all participants who were asked face-to-face, but limited consent for all participants who received forms in the post. It’s a small sample, but it totally makes sense. There is a preference for affiliation and alignment, and so we say ‘yes’ far more readiuly to a human being in realtime interaction. I wonder if there’d be a… Read more »